British composer Steven Price has steadily risen through the ranks of the film music world, beginning as performer, arranger, and programmer for film composer Trevor Jones, moving on to music editing on such blockbuster films as The Lord of the Rings trilogy and Batman Begins, and stepping into the role of composer on such films as The World’s End and Gravity, which has earned him his first Oscar nomination.

What is perhaps most prominent about the score is its heavy reliance on electronically engineered effect-like sounds and its relatively sparse use of music resembling traditional themes. For a disaster film that is about being shipwrecked in space, this may at first seem an odd choice. But since Gravity is steeped in a richly detailed form of realism, true sound effects are minimal and are essentially reserved for those sounds that the characters themselves would hear—rumbles, vibrations, their own breathing, and the like. After all, the film’s opening lines of text remind us that, in space, “there is nothing to carry sound”. In order to preserve the film’s high realism, the musical score therefore adopts a role that would normally be assigned to sound effects. And because the score’s effect-like sounds are not exactly realistic, they contribute more of an emotional impact to the film’s events in much the same way as traditional themes and underscore. The following film music analysis will explore how Price’s use of three recurring elements in the score are a good fit with the film.

Element 1: The “Minor 7th Ostinato”

One of the most pervasive elements of Price’s score is a rising interval of a minor 7th that is employed as an ostinato that repeats after relatively long spans of time (about 15-20s). We hear this ostinato in many scenes, as when the space debris destroys the astronauts’ shuttle, where the minor 7th appears at 0:20, 0:34, and 0:54:

The interval of a minor 7th is one that is only mildly dissonant, so does not create an enormous amount of tension. But with this interval, one can keenly sense the great musical distance it encompasses in moving between its two notes. Along with the slowly looping quality of the ostinato, this element of Price’s score musically reproduces both the vastness and the endlessness of space, a crucial aspect of the film’s impact on the viewer. It is also orchestrated with a trombone-like sound that quickly swells, drops in volume, then fades away in pulsations, an effective way of ensuring a low but regular level of tension throughout the early scenes of the film, where there are long spans of astronauts Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) floating freely through space.

Element 2: The “Clipped Crescendo”

This is by far the score’s most distinctive and memorable element. It is composed of a mixture of sounds, most obviously a jet-engine-like sound, that gradually becomes so loud and so high in pitch as to create an almost unbearable sense of anticipation. It is at the crescendo’s peak, however, that Price does the unexpected and suddenly cuts the music off to silence (or nearly so), making us hyperaware of the lack of sound. This element, which I call the clipped crescendo, is coordinated with two types of events. In some scenes, the coordination is with a collision between Ryan and another object, such as the body of an astronaut that slams into her, or when she careens headlong into the International Space Station (ISS), or even when she hits her head inside one of the stations. The effect is one of emphasizing the feeling of anticipation for the impact, especially for the sake of viewing in 3D, where viewers are immersed into the film’s action in a very vivid way. Here, for example, is the scene of Ryan smashing into the ISS (watch from the start to 0:17):

The clipped crescendo is also used to highlight important events in the narrative. As the film opens with text describing the perils of being in space, then shows the title, the crescendo gradually builds. But just as the first shot appears of a crescent view of the Earth, the crescendo is clipped, ironically suggesting a kind of peacefulness in the shot and establishing a sharp contrast with the disasters that are to follow. Below is the tail end of the crescendo as it leads into the film’s story:

Another important kind of event the clipped crescendo emphasizes is a life-saving change of setting for Ryan. As she approaches the entry hatch to the ISS, for instance, the crescendo begins again, heightening the tension of the scene as we wonder whether she will make it inside with her oxygen tank now completely empty. After she finally does enter, she closes the hatch behind her, the crescendo being clipped exactly at the moment that the hatch is shut, signalling that we can again relax as Ryan is out of trouble, at least for a few fleeting minutes. Watch the scene below (up to 1:00):

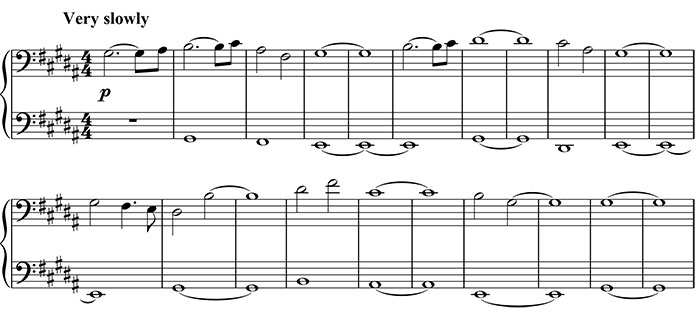

Element 3: The Lyrical Theme

This element is a true “theme” in the usual sense in that it comprises a singable melody with traditional harmony:

Not only this, but the theme is treated as a leitmotif as it is generally associated with Ryan’s loneliness. In the scene below, for example, we hear the theme as Ryan tells Matt about the daughter she lost who was only four years old (watch from 2:21):

Ryan’s feeling of emptiness here is underlined by her admission that she drives around in her car without a destination because she was driving when she received the call about her daughter’s death. Notice not only the theme’s appropriate minor key, but also its scoring for cello, which is a typical instrument used to communicate a character’s tender, innermost feelings.

The theme returns at several other points in the film, for instance when Matt is trying to encourage Ryan to “get on with her life” despite the tragedy of having lost a child. Notice that at the mention of Ryan’s daughter, we hear a soft, elegiac version of the theme sung in a wordless soprano (watch from 2:15; the theme enters at 2:43 in exact coordination with the daughter’s mentioning):

We hear the theme yet again when Ryan is entering the Earth’s atmosphere in an escape pod. But this time, it has been somewhat transformed. Instead of being set in a slow tempo with sparse orchestration, the scoring has been thickened to include several different layers, and the tempo has quickened, enlivened by a driving rhythmic accompaniment. In this climactic scene, Ryan admits that, in this final leg of her journey home, she is ready for whatever is in store for her, whether it be life or death. This new-found acceptance of her fate stands in stark contrast to her description of simply “going through the motions” of life in driving aimlessly in her car. This energized form of the theme therefore draws our attention to Ryan’s change of heart through an example of thematic transformation. View the scene below from 0:44, where the theme makes its entrance:

The theme returns one last time in the film’s final scene, where Ryan emerges from a lake having nearly drowned, drags herself to shore, then manages to muster up the energy to stand and gradually re-accustom herself to walking on Earth again. Ryan’s transition from near exhaustion to walking on land is mirrored in Price’s use of the theme, which makes a similar transformation from its original slow cello version to its full-textured, energetic form (watch from 0:44, where the theme enters):

Conclusion

Steven Price’s score for Gravity can certainly be called unconventional. But as we have seen, its emphasis on effect-like sounds fits well with the film since it allows for a higher degree of realism, the only true sound effects being those that the characters would hear in their limited sound world. The score is therefore used to compensate for the minimal sound effects by coordinating many of the effect-like sounds with action-filled events like collisions and life-saving changes of setting. At the same time, Price does employ the “lyrical theme” as a leitmotif to convey Ryan’s emotional journey (which is of course reflected in her daunting physical journey) from paralyzing sorrow to mobilizing acceptance, rendering the score an unusual, if entirely fitting, blend of techniques both old and new.

Coming tomorrow… Oscar Prediction 2014: Best Original Score.