Upon its release in 1993, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park became what was then the highest grossing film of all time, earning over $900 million at the box office. Its realistic portrayal of dinosaurs through state-of-the-art special effects created such a sensation among the filmgoing public that, when a contest was held to name the new basketball team for the city of Toronto in 1993, fans ultimately chose the name “Raptors” (“T-Rex” was also on the list).

John Williams’ music for the film has become one of his most popular scores, and with good reason. Who could forget its two most prominent themes: the proud trumpet fanfare in “Journey to the Island”, and the more contemplative “Theme from Jurassic Park”. In this post, my film music analysis will take a close look at the construction of the latter theme.

In the film, we first hear the “Theme from Jurassic Park” when Drs. Grant (Sam Neill), Sattler (Laura Dern), and Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) first set eyes on one of the park’s dinosaurs, a brachiosaur feasting on leaves from the treetops. They stare in amazement at the creature, unable to comprehend how such a thing is even possible. And of course at the time of the film’s release, the special effects broke new cinematic ground, so in that way it was easy for audiences to share in the characters’ emotions. But the music also played a large part in eliciting these emotions from the viewer. As he does so often, Williams manages to find the right music to fit this scene. But how exactly? What techniques does he use to give us the sense of awe and wonder that we feel with this scene? Here is the theme in concert version (the portion used in the film begins at 0:47):

Melody

The melody to this theme is based largely on a simple three-note motive: starting on Bb, it moves down to the next closest note, A, then returns up to Bb again (beneath the brackets below):

Although this motive (what is called a neighbor note figure) includes motion from one note to another, the fact that it returns to its starting point creates the feeling that we haven’t really moved at all, especially when it is used in a quick rhythm as it is here. Not only that, but the note that the motive revolves around (Bb) is the key note, or tonic, of the scale the piece is based on. Because the tonic note is usually the end goal of a melody, it is generally a point of rest. Thus, starting with the tonic creates a soothing feeling of calm in the theme. And the repeated use of the neighbor note figure keeps us bound to this tonic, as though we are in a trance with our ears fixed to a single soothing note, just as each character’s (and our own) gaze is fixed in amazement at seeing a living, breathing dinosaur.

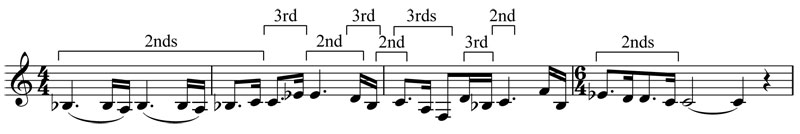

This melody is also written in a very singable way. For one thing, it moves almost entirely in scale steps of a second and small leaps of a third:

There are a few large leaps to be sure, especially near the ends of phrases where they provide a sense of climax to the melodic line. There is also the fact that most of the melody uses relatively slow rhythms (compared to, say, the busy accompaniment figures one sometimes hears running behind the melody). With these singable features, it’s as if the melody is a vocal piece written for orchestra. A real song with words at this point in the film of course would have been a distraction from the dialogue. But an orchestral piece written in a vocal style lends the music a beauty that, in this particular scene, we associate with seeing the brachiosaur for the first time.

Rhythm

The rhythm of this theme also helps us understand why the music works so well with this scene. To begin with, the rhythm of the melody is essentially a more elaborate version of the rhythm in the accompaniment. In other words, when the accompaniment sounds a note, the melody also sounds one at the same time:

This kind of rhythmic alignment between melody and accompaniment creates a very chordal texture that is evocative of a hymn. This reference to the hymn style suggests an experience that is not only positive, but profound—certainly an appropriate sentiment for the characters onscreen.

Another important rhythmic feature of the theme is its reliance on dotted rhythms both fast and slow:

This use of dotted rhythms, especially in this relatively slow tempo, infuses the music with a sense of grandeur and majesty that befits the power and sheer mass of the huge brachiosaur we see in this scene.

Harmony

The emotional content of the theme also derives from Williams’ use of harmony. Most of the chords he writes are the major chords found in a major key: I, IV, and V. And in fact minor chords are banished altogether, leaving the music with a warmly positive sound.

At a couple of prominent moments, Williams also makes use of a chord that uses Ab, which is not a part of the major scale of the theme, but an altered form of the seventh scale degree. Hence it stands out as something strange and otherworldly like the dinosaurs themselves. This chord can be heard in the clip below at 1:34 and 2:44 (to give the chord its proper context, listen from 1:26 and 2:36):

As for the triads Williams uses, there is a strong emphasis on the IV chord, particularly in the progression I-IV-I. Now just to explain here, a IV chord is usually part of the progression IV-V-I, which gives the music a certain sense of forward drive as IV suggests that V will follow and in turn V suggests a final point of rest on the I chord. When IV instead goes to I, that forward drive is replaced with a sense of resolution, giving the music the feeling of calm and restfulness. Of course there are other factors that contribute to this calm feeling, but hear how the chords themselves create this feeling in the clip above at 0:47-0:52, 1:08-1:13, and 1:26-1:32.

Orchestration

Williams’ choice of instruments is another factor that contributes much to the emotional expression of the theme. He begins with an emphasis on the middle to low range of both the orchestra and of the individual instruments. For example, as it is heard in the film, the theme opens with strings, winds, and French horns, but there is a complete absence of any high instruments. So while in the strings, the violas, cellos, and double basses play, the violins remain silent, and in the winds, the clarinets and bassoons play while the oboes and flutes do not. There is also an absence of any loud brass instruments (the horns of course have the ability to play remarkably soft). And a little later on, there is also the addition of a wordless choir. (In the recording above, they are actually singing from 1:08, but are most clearly heard at 2:24). These particular instruments create colors that are not only warm and soothing, but add an appropriate sense of awe and wonder to the music. Williams himself even writes “Reverentially” at the start of the theme.

The Theme as a Whole

As a whole, the theme is somewhat unusual in that it uses the same melodic material throughout—it never diverges from that neighbor note motive I mentioned above. So we are completely focused on the same musical idea, just as we are completely focused on the sight of the brachiosaur.

In addition, the entire theme is divided into two large and similar halves, each of which each of which builds in intensity towards its end (or cadence). As noted above, the theme begins in a mid to low register. The melody in particular begins on the Bb just below middle C, but rises into higher octaves as the theme continues. In the recording below, notice the increasingly high register each time the melody begins a new phrase—at 0:47, 1:08, and 1:26. Also with each phrase there is a louder dynamic, more rhythmic activity, and more instruments added to the texture. All of this reaches a climax at the end of each half of the theme in 1:45-1:55 and 3:01-3:12. The first of these climaxes coincides with the brachiosaur crashing back down to the ground after reaching some leaves high up in a tree. This thunderous impact isn’t just a physical one but also an emotional one, as we marvel at the enormous power of this beautiful creature.

Conclusion

As I have remarked throughout this series of posts, the success of John Williams’ themes can partly be ascribed to his extraordinary talent for coordinating musical parameters towards a common emotional goal. In the case of the “Theme from Jurassic Park”, we have seen the parameters of melody, rhythm, harmony, orchestration, and overall form converge, allowing us to share in the awe-inspiring feeling of the characters who are seeing a live dinosaur for the first time. Now hear the music with the film in the clip below with this coordinating effect in mind:

Coming soon… John Williams Themes, Part 6 of 6: Hedwig’s Theme

The character John Hammond (the genius behind Jurassic Park) and the composer John Williams (the genius behind the music of Jurassic Park) look very similar.

Coincidence? I think not.

LOL! I never noticed that.

one of his best themes i think….has that “inevitable ” quality he strives for…..thanks for this

ed

I enjoyed your analysis of the theme from Jurassic Park. I was a bit surprised that you did not include any references to the English symphonic style of the late 19th century/early 20th century, especially Williams’ use of Gustav Holst’s orchestrational and harmonic style in “The Planets.” The use of the flatted leading-tone chords you referenced (Ab major in the key of Bb) is not infrequent in the music of Holst, Vaughan Williams, and others. Like Holst’s depiction of the immensity of the solar system, Williams chooses this tonal language to convey the immensity of the dinosaurs and something of their regal nature as well. The subtext, in my opinion, is that these beasts were kings of their realm, as Holst’s planets, all named for Roman gods, “rule” their domain in their immensity and grandeur. The music also implies our relatively puny stature next to theirs. Finally, the lowered seventh conveys an exotic mode, rather than the common-practice major/minor system (primarily the Mixolydian), implying a world removed from our own (and perhaps even a sense of anachronism, just as the dinosaurs are an anachronism in today’s world).

Just my two cents’ worth. Again, thanks for your diligent work!

Thanks for sharing these insights, Lester. Yes, surely there is a good deal of Holst, Vaughan Williams, and other composers of that era in Williams. And you make a good case for the similarity between the larger-than-life feel of both Holst’s planets and Williams’ dinosaurs. The thing about Williams is that his music is such a cohesive fusion of so many influences and styles that it is difficult to tease them all out and to say exactly which comes from where. But you’ve given us a glimpse of a likely influence in this case. I agree that the Mixolydian seventh he writes adds an archaic, otherworldly sound, especially given that we’ve been hearing the major seventh up to that point, so its entrance is heightened by the contrast. Also being a sus (or quartal) chord thrown into the context of a very triadic piece, the same note is even couched in a harmony that somewhat stands out. (Though there are a few other such chords before this, these others sound more like triads with dissonance rather than chords unto themselves.) Thanks again for your comments. Cheers.

Thanks Film Score Junkie for your useful post. And the same for you Lester for your comment.

What a valuable information!